Wolfram Language (Mathematica) vs. Python for data science projects

original published: 2019-02-12 for an update see https://thomasgoelles.com/post/math2/

Introduction

There are many blog posts comparing R and Python for data science but there are only a few about Wolfram vs. Python. In this post I will show some differences between Wolfram and Python and presume that you are familiar with Python but not with Wolfram. Python is now the most popular language for data science projects, while the Wolfram Language is rather a niche language in this concern.

The Wolfram Language has been around for over 30 Years, therefore it is actually older than R and Python. The Wolfram language was previously known as Mathematica, which is the main platform for the Wolfram language, besides the Wolfram Cloud and Wolfram Script. Wolfram is widely used in academia, especially in physics and financial analytics. Although I guess the share is dropping also there as Python gets more and more popular.

My first experience with Mathematica was during an undergraduate Maths class where I was immediately impressed by the interactive 3D plots. Back than it was version 5.4, while at the time of writing this post the version number is 11.3 with 12 coming soon. Each major release adds a lot of new functions - in total there are currently about 5000 of them. In Mathematica everything is included from the start and there is no need for import, as all functions are immediately available. If Python comes with batteries included Mathematica comes with the whole battery factory. This means there are no extra packages needed for most of the work, although an in-official package Repository exists.

Wolfram Research, the company behind Mathematica and everything with “Wolfram” in its name, tries to establish that Mathematica is capable of Multiparadigm Data Science. In addition they have announced a Wolfram Data Science Platfrom which I assume to be some kind of cloud service with a lot of automated and pre-defined modules. The platform is “coming soon” for almost 4 years.

However, let’s go back to the basics of the Wolfram language. The general principle is that each function is very high level and automated as much as possible. For example the Classify[] function chooses the method automatically for you, but if you want you can also set it manually to something like Method -> "RandomForest".

The Wolfram Language is very consistent, between functions and also over time. Thirty year old code still works in the latest version. This is not a small achievement (considering the differences between Python 2 and 3) and can mainly be attributed to Stephen Wolfram, the Benevolent Dictator for Life (BDL) for Mathematica and the Wolfram language. In contrast to Pyhton’s Guido van Rossum who recently resigned I expect Stephen Wolfram to be BDL really for life. You can see Stephen Wolfram in action during their live-streamed developer meetings.

So lets talk about the elephant in the room: the price. Mathematica is not free, its actually quite expensive and costs about 3545€ for one license of the standard desktop version. As usual they offer discounts for academia, students (160€) and start ups. If you want to develop a so called EnterpriseCDF that allows to run your code in the free Mathematica Player and access files and databases with it, the price is almost 10k€. Since Mathematica comes with all functions from the start, there is no need to buy additional “Toolboxes” like in Matlab.

There is a possibility to try Wolfram for free, since every Raspberry Pi comes with Mathematica pre-installed. Although the basic functionality is the same, Notebooks are more powerful in the full version and there are of course the speed limitations of the Raspberry Pi.

Examples

In the following sections I briefly show some representative examples. If you want to know more you can have a look at http://www.wolfram.com/language/fast-introduction-for-programmers/en/ where you get an overview of the differences compared to Python and the free book “An Elementary Introduction to the Wolfram Language” by Stephen Wolfram.

Basic syntax

Everything in the Wolfram language is a symbolic expression, like numbers, strings, images, interfaces, code, etc. So there are no “undefined variables”:

Even Plus is a symbol.

Plus[2,3]

Of course you can also write it like this:

2 + 3

Mathematica automatically does the spacing for you as you type.

Or you can also use Apply to, yes, apply the function:

Apply[Plus, {2, 3}]

or in short form

Plus @@ {2,3}

So Mathematica encourages functional programming with Map[] or @ or Apply, Nest, Fold and so on. This becomes especially powerful when using pure functions # similar to lambda expressions in Python.

Lists in Mathematica are written inside {} and the index starts at 1, as it should in every language everywhere and all the time.

list = {1, 2, 3}

firstelement = list[[1]]

firstelement = Part[list, 1]

firstelement = First[list]

firstelement = First@list

The double square brackets are comparable to the brackets in Python. They are the short version of the Part function similar to + being the short version of Plus and @ being the short version of Map.

For complex code you nest functions inside functions which leads to a lot of [], but fortunately Mathematica formats it on the fly in a meaningful way. Nevertheless Python code is easier to read.

A short illustrative example

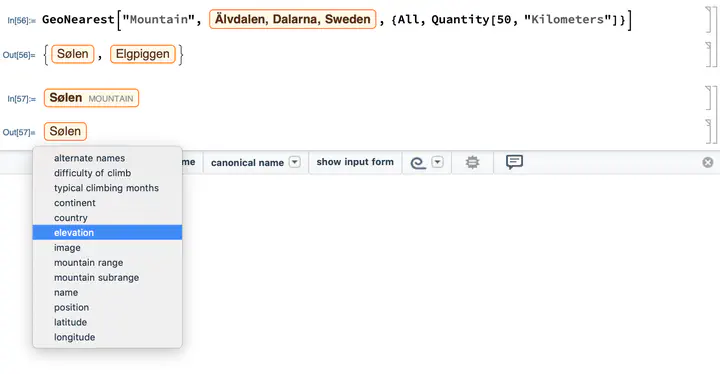

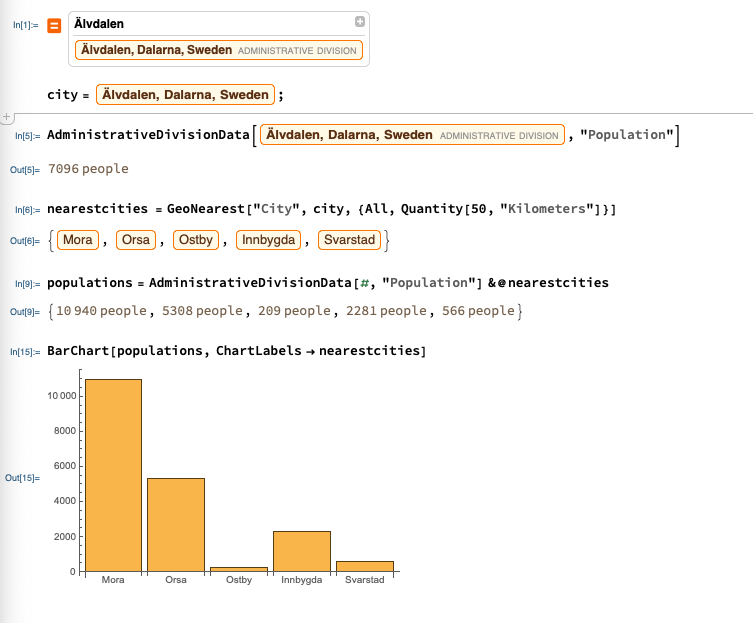

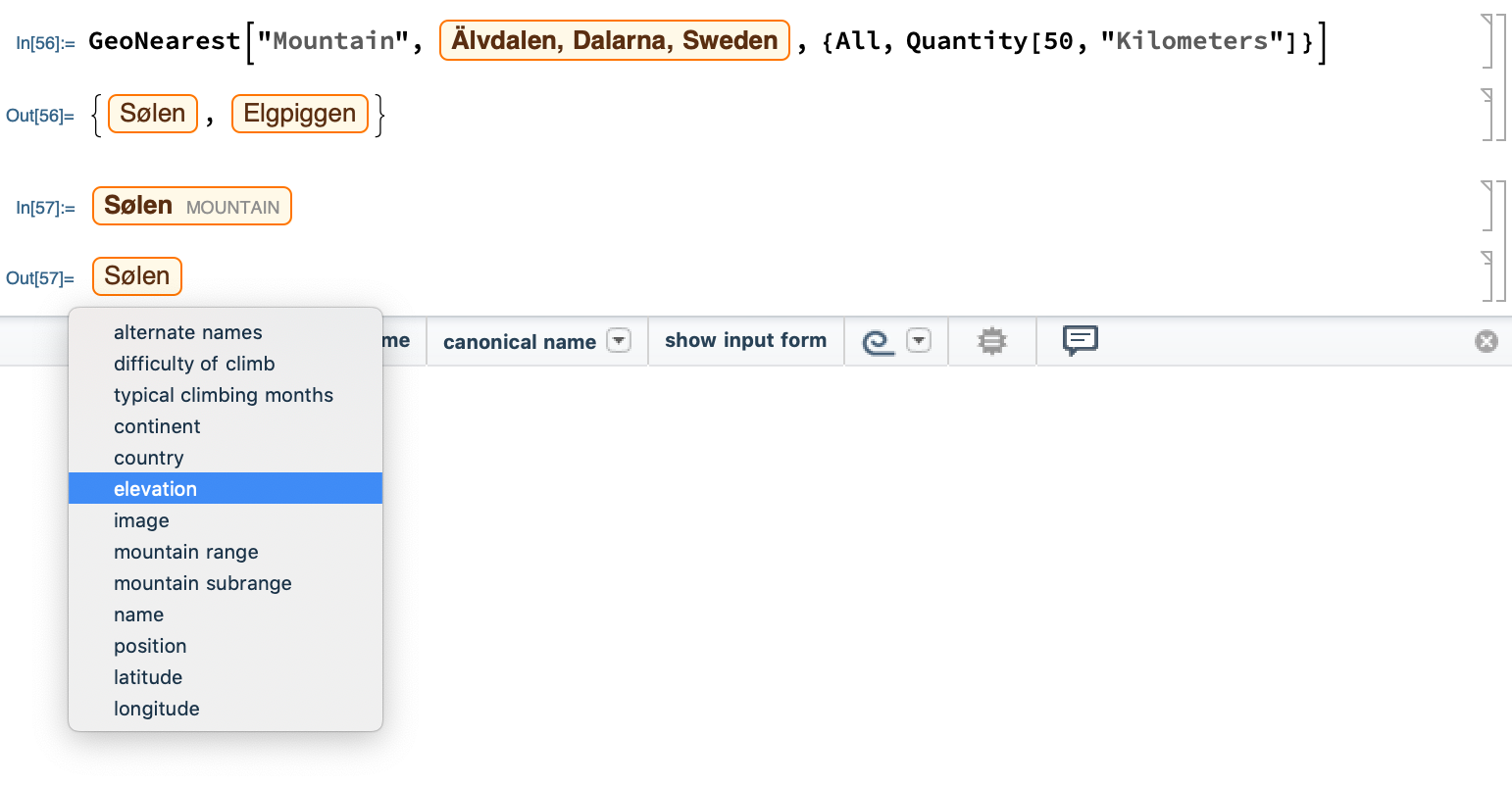

In the following example I will use the built-in data to plot the population of the 5 closest cities near our company location in Älvdalen, Sweden.

In the first line I use natural language to ask for Älvdalen, which returns an Entitiy. There are many different types of entities, like “AdministrativeDivision”, “Dinosaur”, “Glacier”, “Airport” or “ZipCode” and each has a unique set of meaningful properties, like Population for Cities. Wolfram comes with built-in knowledge, the same that powers WolframAlpha. Even the rather small “cities” around us are available.

In In[9] I used a pure function # to extract the population of the city Entity. The population comes with units which are fully integrated in the Wolfram Language. Then finally I plot a bar chart of the populations.

Notebook and Dynamic and Manipulate

The popular notebook format was invented by Stephen Wolfram and still to-date the notebook on Mathematica is more powerful compared to Jupyter notebooks. For example, Mathematica does have more formatting possibilities and a powerful suggestion bar. Although I wish it would support Markdown, which it currently doesn’t.

With Dynamic you can make programming even more interactive, like in this example:

This can by applied to any symbol and with a few lines of code you can get a pretty useful tool, for example for data exploration or to interact with your trained model and you can build a simple GUI in minutes. In my experience this helps a lot in understanding the model and the problem better, since you get a more intuitive understanding. Manipulate is a more high level function and you can build a GUI in just one line when wrapping your trained model in it.

In Jupyter notebooks you can use ipywidgets which I haven’t really tested yet.

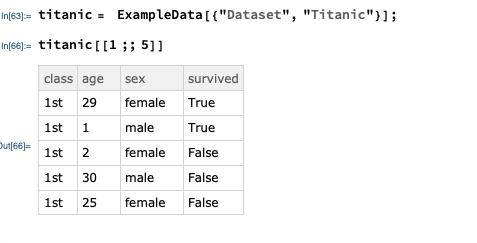

Dataset

The Wolfram language has something similar to a pandas data-frame, called a dataset.

While its similar some syntax is closer to SQL.

titanic[Select[#age > 29 &]]

titanic[GroupBy["sex"]]

I work a lot with datasets but still I need to consult the documentation a lot. An a simple task such as adding a new column can be tricky:

titanic[All, Append[#, "age+2" -> #age + 2] &]

So I would say pandas wins because it is just as powerful and easier to use. Also datasets can be slower to work with, especially for big and nested datasets an Association is much faster. It seems like this might change in the next release of Mathematica.

Machine Learning

The Wolfram language comes with built-in functions which use ML like ImageIdentify LanguageIdentify FindTextualAnswer and high level functions to train your own models like Classify and Predict for regression and the more lower level functions like FindFit and NetModel.

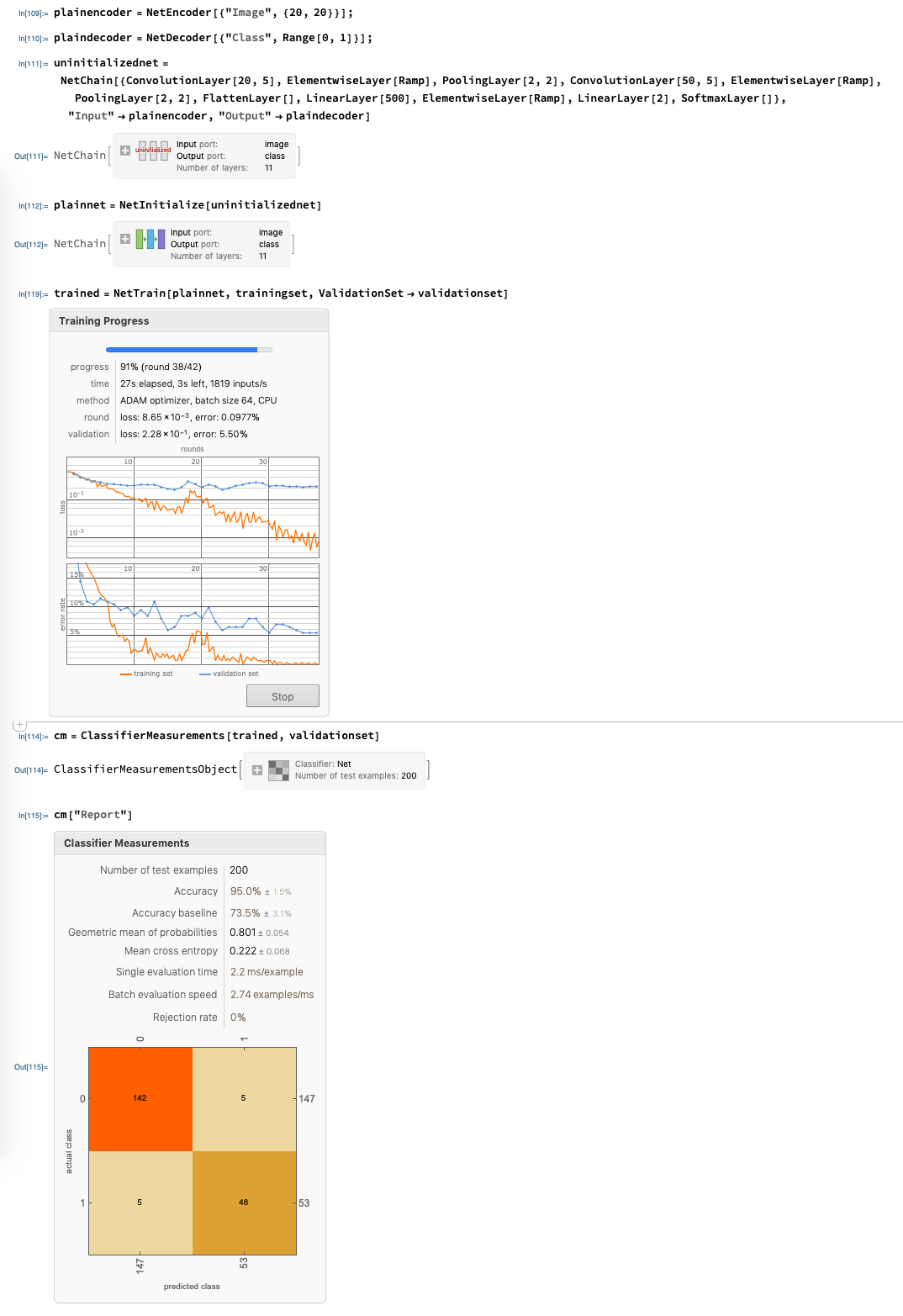

Lets look at an example for a neural network.

The neural network function uses MxNet as a backend and is similar in its use to Keras, although nicer to look at. In general the ML functions in Wolfram have a black box feeling to them, although there are lower level functions as well. In general you should not blindly trust that the automatic solution provided by Predict and Classify is the one optimal solution. They are often far from that and at best give you a base line solution on which to approve on. You can then always use lower level functions to build your own custom ML solution with Wolfram or Python.

Documentation and Community

Mathematica has a very good system for documentation with all built-in functions. Also the documentation itself are notebooks, so you can quickly try something directly inside the documentation.

The documentation in Mathematica is really good, but Python has a much bigger community and it is very likely that you find an answer for exactly your problem. Also you can learn a lot through sites like Kaggle. The Wolfram/Mathematica community is comparably small and therefore it is harder to find relevant information, although the Mathematica community](https://mathematica.stackexchange.com) on stackexchange is really helpful.

Conclusions

Now some bullet points for both languages in no particular order.

Wolfram

- natural language interpretation

- pattern matching is powerful and prominent, for example in function declaration

- interactive and very good documentation

- consistent

- symbolic, you can pass everything into a function (has a lot of advantages but also makes it harder to debug)

- more advanced notebooks

- no virtual environments and dependencies

- works the same in every OS

- most of the time there is only one obvious way to do things, for example plotting

- Dynamic and Manipulate functions for more interactivity

- built-in knowledge

- indices start at 1

- instant API (although only in the Wolfram Cloud or your own Wolfram Enterprise Cloud)

- hard to find a job / hard to recruit people who know Wolfram

Python

- “There is a package for that”

- closer to state of the art

- code is easier to read and to maintain

- debug messages are usually more helpful

- free

- learn from Kaggle

- lots of possibilities to deploy a trained model

- a lot of online courses, podcasts and other resources

- use of google-colab or Kaggle for learning ML without a local GPU

- pandas is easier to use than the “Dataset” in Mathematica

- big community

Learning another language is usually beneficial for your overall understanding of programming. So learning Wolfram might be a nice addition for you. We use the Wolfram language for quick prototyping of ideas and often come up with interesting combinations of data or feature engineering with the built-in knowledge of the Wolfram language. In addition a quick Manipulate is fun and can help a lot to understand the problem and data better.

In Mathematica with just one line you can deploy our model as an API or web-app, although only in the Wolfram infrastructure, which might not fit inside your infrastructure or policy. Also the high level functions Classify and Predict are too much of a black box and even standard scikit learn algorithms outperform them.

Overall I hope that both languages inspire each other, as the jupyter notebook was certainly inspired by Mathematica. For example I hope for a consistent notebook like documentation build into jupyter lab. On the other hand Wolfram will have a difficult future if they continue to try to do everything on their own and lock you into their infrastructure.

PS: for discussion please use use the medium post